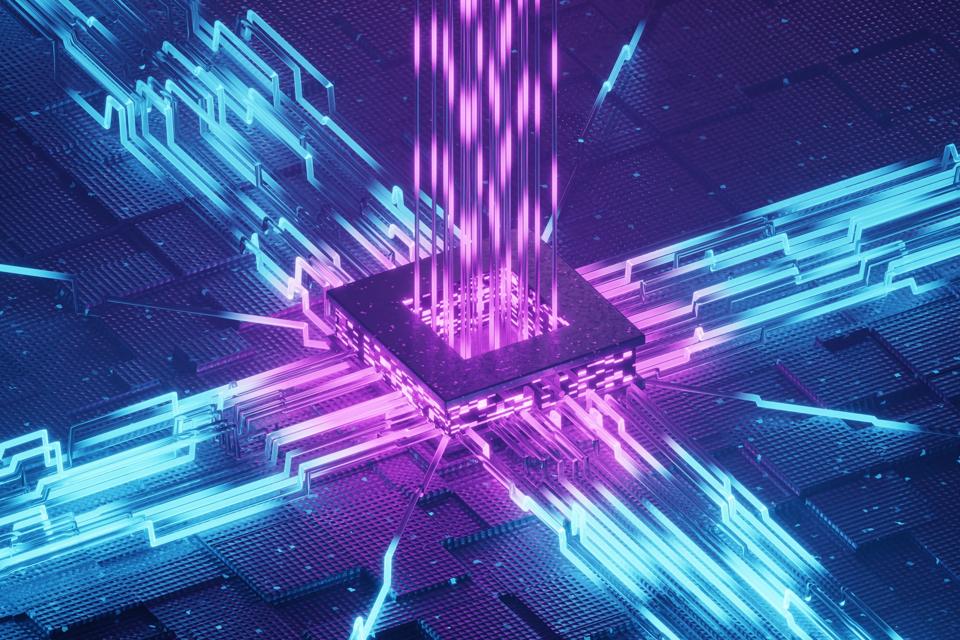

The punishingly cold temperatures and fragile quantum states at the heart of a quantum computer put extreme constraints on the electronics that support them. So far, quantum computing companies have had to solve these challenges in-house, but as the field matures, a burgeoning quantum components industry is springing up to provide off-the-shelf solutions.

Both superconducting and silicon spin qubits–two of the most popular quantum computing technologies–require extremely low temperatures to prevent thermal noise from disrupting their calculations. This means they have to be kept in special dilution refrigerators capable of cooling to temperatures of around 20 millikelvin (-273.13 °C).

These fridges have limited space and very limited cooling power at these extremely low temperatures. Cooling power is a measure of how much heat a device can remove in a certain amount of time, and drops exponentially as temperatures approach absolute zero. Conventional control electronics dissipate far too much heat to be integrated inside these fridges. So instead, quantum computers normally rely on racks of external hardware connected to the qubits via bulky cabling that can also introduce considerable amounts heat into the fridge.

This is an inefficient use of both space and cooling budgets, and significantly restricts the number of qubits that can be squeezed into each fridge. Now though, startups are developing electronics, amplifiers and cabling specially designed for these challenging cryogenic environment. That could enable much tighter integration of qubits and electronics, says Janne Lehtinen, chief science officer at Finnish startup SemiQon, significantly boosting the amount of computing power that can be squeezed inside each fridge.

And this ecosystem of specialized component supplier is emerging fast, he says, mirroring developments in the early years of classical computing. “You had first the few players who did everything, but then when things started speeding up then this was divided into many specialized sectors,” says Lehtinen. “So you didn’t have to be the best at everything but you took the best from the market. And I think this is now starting to happen in quantum as well.”

Sub-zero CMOS

SemiQon has developed a new CMOS transistor optimized for cryogenic temperatures that could allow control electronics to operate in the coldest parts of a dilution fridge. By optimizing the design and materials used to build their transistors, they have managed to drastically reduce the switching threshold allowing them operate at extremely low voltages. This means they dissipate almost no heat, allowing them to work at temperatures as low as 20 mK without blowing the fridge’s cooling budget.

Lehtinen says this could open the door to control electronics that operate alongside qubits, which could significantly reduce their physical footprint and make it possible to squeeze many more qubits into each device. Currently the company can build circuits with a few thousand transistors, which is already enough to create useful components like multiplexers and switches. But within two years they expect to be able to produce a cryogenic microcontroller capable of controlling a quantum processor of around 100 qubits.

Amplifiers that reduce noise

Another key supporting component in many quantum computer architectures, which can also be a major source of heat, is the signal amplifier. The output signals from qubits are extremely weak, which means that they need to be amplified considerably before they can be processed by conventional electronics. But the amplifiers used to boost these signals generate considerable amounts of heat that suck up as much as 50% of the fridge’s cooling budget, says Jérôme Bourassa, CEO of Canadian startup Qubic Technologies, which is developing a novel superconducting amplifier.

Dilution fridges are divided into stages that operate at different temperatures, from room temperature down to a few millikelvin. At the coldest stages superconducting amplifiers based on Josephson junctions are typically used to enhance signals as they generate very little heat, says Bourassa. But they don’t provide enough of a boost to get the signals out of the fridge. That requires a second set of more powerful semiconductor amplifiers that produce tens of milliwatts of heat and so need to be housed at the 4 kelvin stage where there is still significant cooling power.

However, as qubit counts increase the number of amplifiers required increases in lockstep. “At some point, you reach a breaking point where you don’t have enough cooling power accessible to remove the heat from the amplifiers,” says Bourassa. “And so you are now stuck at a limited number of qubits in your fridge.”

Qubic has created a novel superconducting amplifier that doesn’t rely on Josephson junctions and instead uses waveguides made from a proprietary niobium alloy. The design is able to boost signals to the same degree as conventional semiconductor amplifiers, but, because it is superconducting, it reduces heat dissipation by a factor of 10,000, Bourassa says.

These amplifiers can operate at millikelvin temperatures, but current designs produce too much noise to operate close to the qubits. Instead, the goal is to use superconducting amplifiers as a drop in replacement for the semiconductor amplifiers that currently soak up much of the fridge’s cooling budget, says Bourassa. The devices will hit the market in 2026 and the company is already working with leading quantum computer developers.

A flexible cabling solution

The next culprit that is currently limiting the number of qubits that can fit in a single dilution fridge is cabling. Currently, most quantum computers rely on coaxial cables that are bulky and feature a relatively thick metal wire at their core that can conduct heat into the system, says Daan Kuitenbrouwer, chief product officer at Delft Circuits, a Dutch startup developing novel cryogenic cabling.

They also have to be regularly interrupted, both to connect with other components such as signal filters and to cool sections of cable down to the correct temperature for each stage. This can require as many as 20 interconnects that can each be a potential point of failure, says Kuitenbrouwer. “If you cool down a system, the different materials have different thermal contraction so they shrink in different ways,” he says. “If you do that too often, at some point it just wears out and breaks.”

So Delft has developed a superconducting flex cable that is more compact, slashes the number of connections required and significantly reduces thermal transport into the fridge. The device looks similar to strips of flexible printed circuit boards and features eight adjacent wires. In the stages above 4K the wires are made of silver and below they are made from a niobium-titanium superconductor.

Because the wires are much thinner than those in coaxial cables they conduct very little heat into the system, says Kuitenbrouwer, and it also means they can be cooled by simply clamping the flex between two metal parts at each temperature stage. Components like signal filters are also integrated directly into the cable. This means the cable only requires two connectors – one at the top of the fridge and another at the transition from silver to niobium-titanium.

A future quantum motherboard

In the future, Delft plans to use the same technology to create what Kuitenbrouwer calls a “quantum motherboard” – a 2D sheet infused with connecting wires that can integrate various components at cryogenic temperatures. The company is banking that future quantum computers will follow a chiplet architecture with multiple smaller quantum processing units and cryogenic control electronics all integrated on the same chip.

“You get this whole zoo of different functional components that all have to be connected to each other,” says Kuitenbrouwer. “So what you basically need is very high density, very low loss interconnect, and that is what superconducting flex can offer.”

Tying all of these emerging component innovations together though is the need to save both space and cooling budgets. For Qubic’s Bourassa, that’s the only way the quantum industry is ever going to achieve the scale necessary to fulfill its lofty ambitions. “Having the capacity to remove the heat, having the capacity to make your systems more compact is definitely the pathway towards something that is viable in the future, both in terms of power but also economically,” he says.